"Theology is that science which treats of the unknowable with infinitesimal exactitude."

Amen.

ó

As Liberia elects the first African woman head of state in history, I can't help but take some delight in the symbolic symetry of the event, Liberia having also been the first African nation to gain independence from European style imperialism.

How poetic!

ó

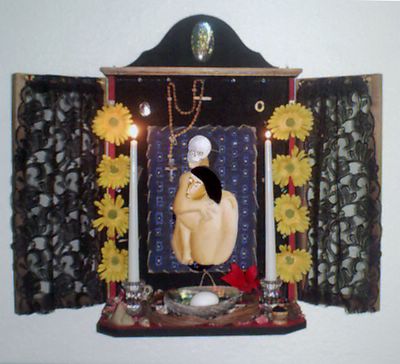

This year, for Dia De Los Muertos, I built a shrine dedicated to the memory of those who fell during the conquest and colonization of the Americas.

In fifteen-hvndred and six

Colvmbvs crossed the river Styx.

Did he know what he wovld find

When he left Madre España behind?

(i pledge allegiance to yovr flag

and all that jazz aside)

Trve north waiting?

Perhaps a pear-shaped world,

(Like a woman's honey breast)

Great golden calves to fatten and gorge on,

Vast watery doldrvms

In which to kill time,

The endless sea . . . .

Thursday, November 3, 7pm

sunflower

© 2005

I was having lunch recently with a fellow musician friend. At one point he told me that he was considering going back to school to study music theory. I like music theory, I've spent many hours navigating it. What struck me as odd about his comment, though, was that he cited as his main reason for taking theory courses the fact that he wants to learn how to compose. This makes very little sense to me. Theory as I see it is just a way to catalogue and describe all the different ways in which composers and musicians have put music together, all the names that they've given to the many conventions: the German 6th, the half-diminished scale, the breakbeat, . . . the two-five-one's of it, you might say.

I didn't dwell on it, but the fact that someone would use or even see theory as a "how to" is mildly amusing to me. Mechanistic composition. The root of serialism? Hmm. Duke said, "if it sounds right . . . it's right." I agree.

It makes me think about something T. S. Eliot wrote about the study of poetry.

I have never been able to retain the names of feet and meters, or to pay the proper respect to the accepted rules of scansion . . . . This is not to say that I consider the analytical study of metric, of the abstract forms which sound so extraordinarily different when handled by different poets, to be utter waste of time. It is only that a study of anatomy will not teach you how to make a hen lay eggs . . .

"The Music of Poetry"

amen to that . . .

I have a friend named Mark Manley who I haven't seen in years. He liked to play a flailing rubberband sounding bass guitar way back when I knew him. I remember that one of his favorite aphorisms was "A writer writes!". He would say it with a facetious tone.

He was indirectly poking fun at student mindset - people trying to learn to write by the book. If you want to learn about plot or character development, read some good work. That's the point. Although simple life experience is a better tutor, the reading we do is a pretty good teacher. The former provides us with content, the latter informs our forms. Delight in letters is what inspires the writer.

Who was it that said that a writer is nothing but a reader moved to emulation?

A wise fellow.

peace

ó

1 - heathens - (5:15)rob fix - bass | 6 - (let) X=X - (4:06)kate russo - violin |

| 2 - spike & the slydog (américan roulette) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . - (4:29) peter venti - piano | 7 - reach - (4:36) *chant peck & scott nowak engineered |

3 - man in the water (building a fire) - (3:45)darell colton - bass | 8 - the river - (6:17)peter venti - keys |

4 - on a rainy day - (2:59) *chant peck & scott nowak engineered | 9 - summerland - (4:41) peter venti keys |

5 - the mark of cain (4:55) *chant peck & scott nowak engineered | 10 - magdalen blue - (5:56)darell colton - bass |

Yesterday I went to go hear Robert Bly read from two of his recent volumes, one an anthology of his translations (The Winged Energy of Delight) and one a book of his own ghazal verses (My Sentence Was A Thousand Years Of Joy). He wore a colorful ornate silken jacket of asian origin and smiled a lot. Now seventy-eight years old, his head is crowned by a thick mass of white hairs, credentials of his humanity. What a beautiful man.

I'll just let him him speak through his poetry, and simply add that he moved me.

The Night Abraham Called to the Stars

Do you remember the night Abraham first saw

The stars? He cried to Saturn: "You are my Lord!"

How happy he was! When he saw the Dawn Star,

He cried, ""You are my Lord!" How destroyed he was

When he watched them set. Friends, he is like us:

We take as our Lord the stars that go down.

We are faithful companions to the unfaithful stars.

We are diggers, like badgers; we love to feel

The dirt flying out from behind our back claws.

And no one can convince us that mud is not

Beautiful. It is our badger soul that thinks so.

We are ready to spend the rest of our life

Walking with muddy shoes in the wet fields.

We resemble exiles in the kingdom of the serpent.

We stand in the onion fields looking up at the night.

My heart is a calm potato by day, and a weeping

Abandoned woman by night. Friend, tell me what to do,

Since I am a man in love with the setting stars.

He brought along some copies of a slender book of poems against the Iraq war he published called The Insanity of Empire, and gave one to me.

I've never seen the Survivor show but I'm a sucker for trivia games so I'm taking part in an online version of it in CC2. The very first question asked in the game brought my attention to a problem which I encountered a few years back in a different setting. Back then I was surfing around one night and came across an apologetic/polemic website whose whole purpose was to catalogue and comment on various apocryphal and extracanonical ancient texts. Early into my exploration of his site, though, I began to notice errors.

For example, he said that the Gospel of Thomas contains some stories in which Jesus is depicted as a spoiled brat of sorts. In these stories, the excitable and capricious boy Jesus, when angered, could become vindictive and even very violent. As punishment for one of his playmates' messing up his fishing pool, for instance, he causes the kid to instantly wither like he did the fig tree on the way to Jerusalem in the synoptic Gospels. After the townspeople complain to Joseph and Mary about it, Jesus restores the kid (although he leaves his hand withered as a warning). Later in the same chapter Jesus makes another kid drop dead for bumping into him in the street and makes all those have a problem with that blind (at which point it is recorded that Joseph pulled Jesus sternly by the ear for his behavior). If one is not familiar with these texts, it will come as a shock that these kind of stories were actually common once upon a time.

These stories do exist and they go way back. The trouble is they don't come from the Gospel of Thomas (GTh) as this guy claimed in his website. When NT scholars refer to the Gospel of Thomas, they mean a very specific text. They are talking about a collection of one hundred-fourteen sayings of Jesus of which a complete copy in Coptic was finally unearthed in 1945 near Nag Hammadi, Egypt. We also have two fragments in Greek which were discovered in 1898 and which are older than the Nag Hammadi copy. The GTh contains nothing at all about the acts of Jesus. There are no signs in this gospel, no wonders, no virgin births, no Josephs, no Maries; it's just a list of sayings spoken by the "living Jesus". The story of a bratty Jesus comes from another book altogether, a book traditionally called The Infancy Gospel of Thomas (or Infancy II -- to distinguish it from the Protevangelion, or Infancy Gospel of James, and there's even another Infancy Gospel, Infancy I, which, curiously enough, is also attributed to Thomas, as if it wasn't confusing enough already). Infancy Thomas probably dates from the third century. Only a fragment of it has been preserved.

¿So why do I bring this up?well . . . This week, the trivia question was: "What flower is usually associated with St Joseph and why?". Some of my teammates knew the first half of the answer : the white lily which sprang from his staff as a sign of his selection as Mary's husband. But where did this legend come from? None seemed to know. Aha! I was on the case! I figured I'd look at the Protevangelion first. This is usually where miraculous perpetual sanctities regarding Mary are first spoken of but, to my surprise, the story in the Protevangelion speaks of a dove springing from his staff as a sign of his selection as a suitable husband for Mary . . . not a lilly. Hmm . . . So I turned to the infancy gospels next. Nothing there. Oh shit!, don't make me have to read Jerome again! (not my favorite founding father to read . . . laughs). Luckily, it was then that a teammate found the vital link. She found a quote which claimed to be from the "Gospel of Mary" which contained the legend. Great! So I turned to the Gospel of Mary. But . . . . there was nothing there, the quote didn't match . . . .

Wait a minute! . . . . What's going on here? Imagine that someone quoted a saying in Matthew, and when you went and looked for it in Matthew . . . . it wasn't there!

Luckily, she provided chapter and verse numbers which helped me to cross-reference between books and, after a little searching, I finally found it. The source is an ancient text that was attributed to Mathew back then, which is called The Gospel of the Birth of Mary. Most likely a third century work, it was used by Jerome extensively in his writings. Ah! But wait! . . . In some of the secondary sources, this book is refered to as the "Gospel of Mary". Ah! So here's where the rub started! . . . . from an abbreviation!

When modern scholars speak of the Gospel of Mary, though, again, they mean a specific book of which only three fragments have survived into our modern era, two in Greek (its original language) and one (the longest fragment) in Coptic. This work can arguably be dated to the beginning of the second century, which would make it as old as much of the NT. The Mary that is refered to in the title and who is the focus of its text is not Mary the mother of Jesus but Mary of Magdala. This gospel is a fascinating glimpse into some of the conflicts that arose between early variants of the nascent movement when trying to determine and assert apostolic authority. In fact, I think it's in some small part because of its undeniable antiquity and because of the import of its content that Pope John Paul II was moved to proclaim Mary of Magdala the Apostola Apostolorum, the apostle to the apostles.

But all that aside, the Gospel of Mary contains nothing at all on Joseph. . . . is my point.

So what's the big deal?Well, like in the above GTh example, it's just a bad reference. Bad scholarship.

Now . . . You might be thinking . . . "Everybody's human, though and we all make mistakes, most of which are pretty benign anyway."

¿Right?

Sure. . . okay. . . but. . . if you believe that . . . . then ask yourself how you feel about things like the Da Vinci Code. Should we just let that slide? That seems to me the perfect example of conjecture and erroneous information being passed off as "history" to a welcoming public raised on controversy. The following two responses are certain:

1 -- Those who are pious and strong in their faith will trust their priests and pastors on their word as to the worth of the conjectures and the questions raised by them.

2 -- Those who know that David Brown is trying to pass off wild speculations and conjectures as factually verifiable, because they have taken the time to read and critically examine the germane texts, will simply find him amusing.

But what of the everyday people (mostpeople) who take their quasi-faith solely on faith, those to whom these things are far-off academic matters, those who have more pressing things to do in their living than check on the historicity of things? Either they succumb to their reptilian need for gossip and scandal, and thus buy into spurious claims like those in Brown's novel, . . . or else their incertitude leads them to a kind of cynical position in which the baby (honest historical research) is thrown out with the bathwater (Da Vinci Code-like misrepresentations) without further thought. It's not hard to imagine that, upon hearing that the Gospel of Thomas contains stories of a mean young Jesus who kills children who piss him off . . . . . . well . . . a person might easily dismiss that out of hand, and then close his or her mind off to even looking at the GTh (a turnoff from the git go is seldom overcome -- an example from recent politics: Senator Kerry couldn't rebound from false accusations of treason and suchlike -- the last presidential campaign was a shameful affair in this respect, but I'll save that for another post) even though it's simply not true that there are any such stories in this text. That's what worries me about these historical fabrications, that ordinary people will not be able to distinguish between honest methodical work and sensationalist musing or reactionary rhetoric.

The curent Da Vinci Code mass credulity kinda reminds me of the movie Amadeus. In that enormously popular oscar-winning film, the court composer Antonio Salieri was portrayed as an envious contemporary who was moved by this envy to calculate and then bring about Mozart's death.

Great story. . . . ¿Right?

Yeah, except it's almost certainly not factual. Such fanciful rumors of the mysterious circumstances surrounding the death of famous historical figures like Mozart abound in our histories:

e.g.

Akhenaten's murder

Robert Johnson poisoned by a jealous husband

Warren G Harding's wife suspected of having had him killed

Tiberius' exit vs Gaius' entrance

Pope John Paul I rubbed out for his liberal views

Courtney Love vs Kurt Cobain

the Kennedys

Jesus

. . . . the list is long

Or take Lizzie Borden, of macabre nursery rhyme fame, as an example. It turns out she was taken into custody, tried, and released after it was determined she had nothing to do with what she is now famous for.

. . . . . . . (or why I love the innocence mission)

Let me first say that I can't stand "christian" music. It makes me wince. I've tried to not involuntarily respond to it like this, that is, to not kneejerk -- to no avail; I just can't stand it, no matter how hard I try. Now, mind you, that's not to say that I have anything against musicians who are christians by faith; that's not what I'm saying at all, lord knows I don't care what religion one holds in one's heart of hearts, as long as one is honest to oneself and to others. God is Truth is Love is Beauty, and everybody knows that beauty wears many different liturgical robes, so I guess what I really object to is the category of "christian music." I don't mean gospel music by this, incidentally. Mahalia Jackson, James Cleveland, Pops Staples, for example, are all fine artists within that genre, and have kept the tradition going. I have nothing against this christian music. No ... by "Christian Music" (X-stian, henceforth to denote the difference) I mean the genre that has established itself in the last couple of decades as an alternative to "secular" pop and rock and hip hop music. Evangelical and other zealous types figured they could adopt our modern dance forms, change their lyrical content and use them as tools for evangelization. We now have new & improved, cleancut nutrasweet versions of our pop musics, replete with inoffensive language and good old-fashioned edifying moral values. This is all very well-meaning and even a good idea, until one realizes that that which makes our modern popular forms so special is precisely that which makes them dangerous and subversive. A sense of daring. Take that away and all you have left is empty posturing. A mere facsimile of art. (and this is just the lyrics . . don't get me started on the music)

Put another way: Most X-stian music makes me feel like I accidentally walked into a national convention of Elvis impersonators.

By contrast, let me now say that I love the music of the innocence mission, a family of musicians from Lancaster, PA. who by their own admission are unashamedly good christian people (Roman Catholic, in fact). I have met them and can attest to their kindness and their mildness of manner and style, their grace and their undeniable deep rooted sense of spirituality. I have been a great admirer of their work for more than a decade and have always felt a certain kinship with their music. The truly amazing thing to me (and the crux of this post -- why I bring it up) is that, until they devoted a whole cd to their favorite hymns and devotional songs a few years back ("Christ Is My Hope" -- a benefit recording they made to raise money for a local catholic charity), they had used the word "Jesus" only once in all their previous releases. Yet I hear in their music a depth of spirituality that makes the formulaic platitudes of most X-stian music sound as inspired as the scripted spiel of a used car salesman. Their outlook (i.m.'s) is unmistakably christian, but it's expressed in soft washes of humility and grace and wonder. Easy on the preaching, theirs is a music that celebrates the world by taking delight in the simplicity of moments, a music that somehow manages to simultaneously evoke both joy and melancholy.

| "In this story we sit down on Luna Bridge, and catch snow in our cupped hands and music is coming from the houses, or it sits inside me . . . " | "You go outside. You see the holy spirit burning in your trees and walk on, glowing with the same glow . . . And the birds of all your yellow teacups sing, and you know this hymn . . . " |

I find solace in music that challenges one to think about what it means to be a spirit-filled being in these post-post-modern times. Now as ever, joy comes to us in little packets like these each and every day. In our homes and in the faces of our friends and families. You can miss these tiny miracles if you are not paying attention.

In our living -- this is where spirit resides.

I don't think they consider themselves an X-stian band. I think they've even consciously avoided such a limiting categorization and I applaud their integrity. I'm certain that they would find a ready-made market just ripe for the picking if they ever decided to walk such a disingenuous path. I certainly wouldn't fault them; money talks loudly. I'm glad they haven't succumbed, though. The narrow market perspective that demands the same devotional catchphrases, the same aphorisms, the same old same-oldisms, keeps performers churning out the same song over and over again. It's refreshing to see an artist daring to do elsehow . . . taking the "road less taken", as Robert Frost once called it.

The other day I found the following paragraph in the introduction to the "Oxford History of Christianity." Reading it made me think about the interrelation between art and the spirit.

"Christianity is a religion of the word -- the 'Word made Flesh', the word preached, the word written to record the story of God's intervention in history. Every story needs a picture. Pope Gregory the Great defined the role of the artist thus: 'painting can do for the illiterate what writing does for those who can read'. Augustine had gone further in praise of music: written words are in themselves inadequate -- 'language is too poor to speak of God . . . yet you do not like to be silent. What is left for you but to sing in jubilation'. The visual artist as well as the musician is entitled to the benefit of the Augustinian argument. Words constitute a record exerting a long-term pressure: a work of art has an instantaneous impact. It bridges the gap between cultures with a simple gesture with an immediacy denied to translations of the record. Whatever the culture from which it derives, a great work of art is a potential source of spiritual insight, falling short of words in the power of syllogistic argument and even in the ability to suggest the content of the imagination's inward eye, but far superior in the evocative power to haunt and illuminate. Wassily Kandinsky, the pioneer of abstract painting, who published a study of The Spiritual in Art in 1912, spoke of art as resembling religion in taking what is known and transforming it, showing it 'in new perspectives and in a blinding light'. Some of the masterpieces of painting and sculpture in the Christian tradition have been produced by artists whose status as believers is doubtful. In Kandinsky's view of the breakthrough to spiritual perception, this is no paradox. 'It is safer to turn to geniuses without faith than to believers without talent' (my emphasis), said the French Dominican Marie-Alain Couturier -- an aphorism which he tested by persuading Matisse, Braque, Chagall, and other great names of the day to do work for the church of Assy in the French Alps. Couturier was not subordinating religious considerations to élitism; to him, 'all great art is spiritual since the genius of the artist lies in the depths, the secret inner being from whence faith also springs'. Jacques Maritain has drawn out a further implication of the supposition of the unity of all spiritual experience. To the Christian who wishes his art to reflect his religious convictions he says: keep this desire out of the forefront of the mind, and simply 'strive to make a work of beauty in which your entire heart lies.'. (my emphasis)"

Amen to that . . .

The X-stian music category is full of "artists" who seem to only want to express devotion to their chosen faith. They just praise, as if that is solely what worship consisted of. They sing, "O, lord how I love thee", over and over and over again, and say little else, unfortunately. This to me seems like a wasted opportunity. It's as if they think that their good intentions are enough to safeguard the quality of their artistic expression.There's the difference..

These two films will be shown in anticipation of the "Surrealism U.S.A." exhibition. This introduction to surrealist film begins with two collaborations by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí, Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog) and L'Age d'Or (The Golden Age).

Yesterday I attended a public symposium on religion, science, technology, and law that was held at ASU' s Tempe campus. It was sponsored by ASU's Center for the Study of Religion & Conflict.

By my estimation, approximately 500 people attended. The average age of the audience was considerably higher than I would have expected, but there was a good cross section of the community represented in the audience nevertheless.

Ronald Green and Larry Arnhart touched on some of the ethical issues raised in the field of genetic research and their implications for our culture.

brief intermission

Philip Clayton and Carl Mitcham then discussed the ethical and practical concerns of the religion/science divide from a technological perspective.

These professors for the most part all shared the view that the traditional chasm between religion and science can be bridged. They agree that technology and the aquisition of knowledge in general is inherently a good thing (with the exception of Dr Mitcham, who described himself jokingly as the "luddite of the bunch" several times during his segment) but they point out that our accelerated rate of progress is now such that it's remarkably easy for some to envisage images like those in Aldous Huxley's "Brave New World", in which the genetic and pharmacological and pedagogic sciences are used as malevolent controling forces in society. An evil technocracy awaits us, they warn. "Not if we can help it", our lecturers boldly claim. They agree that this fear and apprehension that some feel at what they see as an attempt by Science (with a big S) to "play God" are not really rationally defensible (doomsday scenarios never are), but while it is true that we should not ignore the difficult ethical issues raised in these matters, it is unwise (I agree) to hastily adopt an overly pessimistic attitude toward progress. To paraphrase the best line in Dr Green's lecture, we should not be imagining nightmares when we should be cultivating dreams.

The panelists all seem to trust that "human nature" (a phrase that was not adequately defined) is enough to safeguard us against the very things which we fear. In other words, they trust that people won't abuse the new technologies, simply because we all deep-down just want what's good for our children and for our societies.

This point seemed to me somewhat naïve and needs to be addressed more fully and directly. It completely disregards the lessons of history. Human nature may make us benevolent, but seldom to the point of eliminating our basic selfish tendencies. Our vanities.

While it's true that everyone wants the best for their children . . . . . . the best intentions do not guarantee that we will make the right decisions, particularly as it pertains to favoring our own. It may be cynical on my part, but I DO believe people will be tempted and will have a tendency to abuse the technology just so their darlings will be taller, stronger, faster, prettier, smarter . . . whatever . . . . anything that will give them an advantage in their athletic, artistic, academic, or even merely aesthetic aspirations. While I agree that we should be generally optimistic about our role in history and about the continuing advances in the science of information transfer and of biology, when it comes to cases involving eugenics or cloning or genetic engineering, we must be extremely cautious. We have to vigilantly and critically examine the legislations we enact today, precisely to ensure that their abuses will be rare and few tomorrow.

Another related topic discussed by the panel was the subject of embryonic stem cell research and the obstacles being erected in our nation to impede its progress. This year, as we celebrate sixty years since Dr Jonas Salk's research gave us the vaccine which all but eradicated polio from our human experience, I doubt anyone would dare say that his work was anything but a marvelous gift to mankind. It's a little known fact, though, that the tissue which the good doctor used for his specimens was, in fact, mostly fetal tissue. Ironically, in our current climate of reactionary political divisions, it is sad to think that, today, Dr Salk's research would not only not be funded, but might even be outlawed outright.

peace